|

__________________

How America Can Replace Wall Street Financing with

Public Banks

By Marc Armstrong

Executive Director, Public Banking

Institute

This article was adapted from a speech Armstrong gave at the

Progressive Festival in Petaluma, California, on Sept 15,

2013.

Occupy.com

Many of you have likely heard about public banking and how

it is central to many developed economies in the world, and

the dominant model in others. Germany has public banks

funding much of their manufacturing sector as well as their

rapid installation of renewable and distributed energy

production systems.

New Zealand has a postal bank, which they use to provide

convenient and low cost banking services to their people.

China has the largest development bank in the world. Japan

has the largest public bank by deposits in the world. India

has the largest public bank, in terms of its number of

branches, in the world. And Scotland has the largest public

bank by assets.

And the United States? Our country is bereft of public

banking and true public finance. Sure, we talk about public

finance as if it serves the public, but the reality is that

virtually all of our public finance has been co-opted by

private banks. With the exception of North Dakota, all state

treasurers deposit their state tax revenues and fees into

private banks — usually the ones on Wall Street, setting the

stage for endless dependency on the private banking cartel.

We've been led to believe there is no alternative. Take, for

example, the California Infrastructure Bank, or I Bank. An I

Bank is a public entity that uses private money to fund

public projects. On the face it it, this seems like a good

approach — not using taxes to fund public projects. But the

reality is that the I Bank is another form of hidden

taxation, in the form of interest payments, making wealthy

people wealthier by teeing up safe, long-term investments in

public projects like bridges and other infrastructure.

The San Francisco/Oakland Bay Bridge was initially funded

with the I Bank. Ignoring the twists and turns of the

planning process during the 90's and the last decade, the

new bridge is a safe investment; the money will undoubtedly

be paid back by tolls. The cost for this new bridge is $6.4

billion, a sum widely quoted in local papers. What is not

said is that the interest and fees for this will be another

$6 billion. $6 billion to be paid until the year 2049.

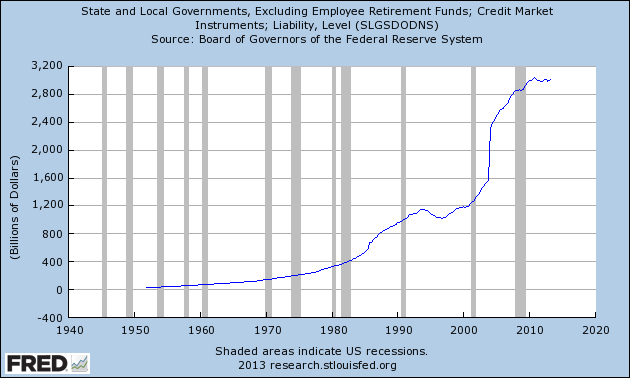

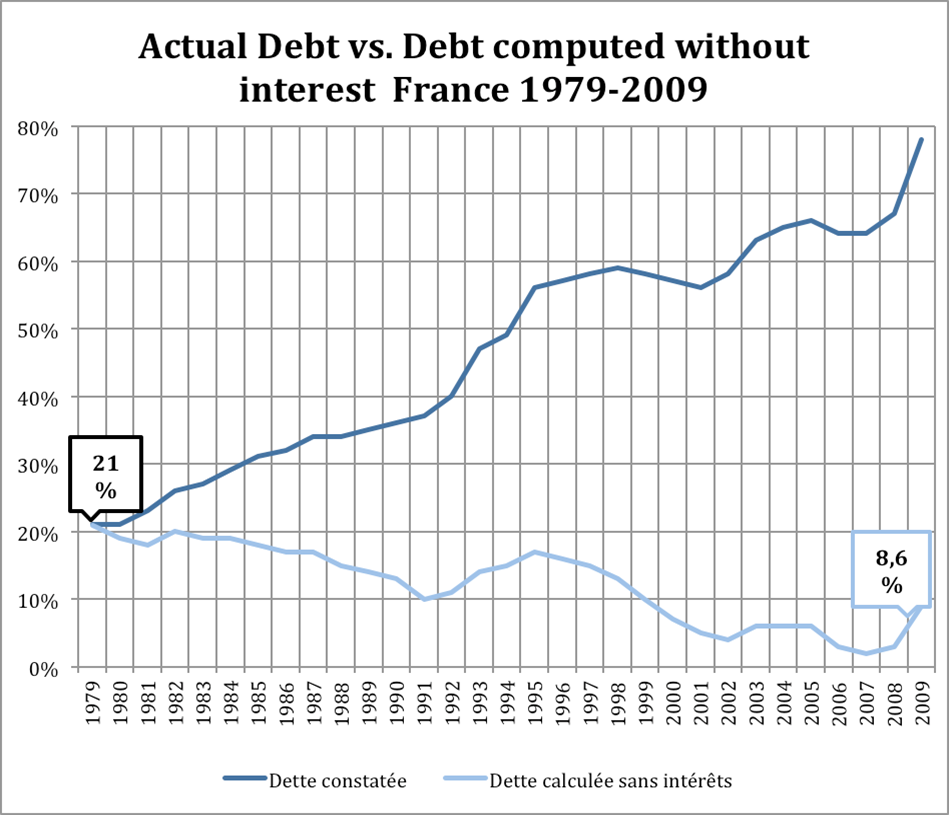

This is a good time to ask why we hold labor costs under the

microscope and rarely do the same for debt servicing costs?

Ask your local elected officials; do they know the debt

servicing costs in their budget? I suspect that many of them

know, to the penny, what the labor costs are.

This is now playing out in Detroit where pension plans are

readily placed on the altar to be sacrificed, but what is

due to the banks is sacrosanct. Yet North Dakota, the only

state in our country with a public bank, does not have debt

servicing costs because they "don't spend more than they

take in," or so the locals like to say.

The reality is that North Dakota doesn't issue general

obligation bonds because the state has its own bank to

finance public infrastructure. Last year their public bank,

the Bank of North Dakota, issued a $50 million loan to fund

a new water pipeline. The paid interest on this loan is

reported as profits to the bank and — guess what — it gets

returned to the state general budget, benefiting the very

same people who paid for the water.

Meanwhile, in California, public finance is being starved

for funds. Earlier this year, California Watch published a

study that showed that over the last six years over $9

billion in loans have been taken out as "capital

appreciation bonds" by our school districts to fund school

construction and improvements. The estimated cost in

interest: over $26 billion. In other words, we are

obligating future taxpayers, our sons and daughters, to pay

$35 billion for our use of $9 billion today! What kind of

legacy is that?

Elected officials cannot raise taxes; they've cut as much as

they can cut, many districts are bonded out, they've reached

their debt ceiling and are privatizing whatever they can for

short-term gain. So, what options do they have other than to

take out these toxic debt products peddled by Wall Street?

It does not have to be this way. Your treasurers at city,

county and state levels can easily take public monies that

are on deposit in Wall Street banks, deposit them in a

public bank and use the bank credit for the public good.

If we had a state Bank of California, the state could have

funded the entire $6.4 billion bridge construction cost

simply with bank credit generated by state deposits. Think

of that the next time you pay the $6 toll on the Bay Bridge

— knowing that over 55% of that money is going toward

decades of interest payments to the big Wall Street banks.

A state public bank means the state gives itself a license

to issue credit through use of deposits. The "bank" is

simply a few cubicles staffed by people who understand

credit and interest rate risk. But the heart of it is the

license, issued by the California

State Department of Financial Institutions. This

can be done at the county or city level and can effectively

eliminate debt servicing costs, a major line item in the

budget.

Public banking is all about economic sovereignty and self

sufficiency. It is about sharing the exclusive privilege

that we, as a people, have given banks to use bank credit,

issuing loans simply by writing them into their books.

We recognize that in a free market there are essential

public utilities that exist side by side with well-regulated

products. Tap water at low cost exists side by side with

more expensive bottled water. Electricity provided over the

wires exists side by side with power generators. Mass

transit exists as an alternative to using expensive cars,

and are complimentary. 44-cent first class postage through

the US Postal Service exists side by side, for now at least,

with $17 overnight delivery through FedEx.

We are so used to banks being the exclusive provider of bank

credit that many of us don't even recognize that we can

create an alternative. Fortunately, most other

countries,have not been snookered the way we have. They are

not paying FedEx prices for public finance.

The Public

Banking Institute's vision is to see a network of

public banks — 50 state owned banks and scores of county and

city owned banks, with the US Postal Service additionally

providing core, low cost banking services to 10 million

currently unbanked people and over 20 million who are

underbanked — established throughout the United States.

Not only can this network provide low cost banking services

and affordable credit for infrastructure financing and to

create jobs, but it can also provide LIBOR-like interest

rate benchmarks that can be used instead of relying upon the

private banking cartel for this important index.

Even more important, our vision is for the self sufficiency

of our communities. Do you want your county to reduce its

carbon footprint? Start a loan program to improve the energy

efficiency of homes. Sonoma County in northern California

did this a few years ago, but did it with tax assessments on

property bills. The costs for the Sonoma County Energy

Independence Program (SCEIP) could have been much lower with

a county owned bank. The Bank of North Dakota has 26 of

these loan programs.

Do you want to see your county build or extend mass transit,

clean water, clean energy, etc? Fund these projects with a

county bank, and every one of these loans will be self

liquidating — paid back with the fees generated from the

service provided.

So, if you're looking for one cause to take on that truly

changes the way our society works, pick up public banking in

your city or county. Austerity, the fiscal cliff, the

dominating headlines that scream “We're Broke!!” — these are

all myths, and they are being steadily, increasingly

revealed as such. Challenge the Wall Street cartel of

private banks and you will be contesting with the most well

financed lobby the world has ever known.

But you will be acting as a citizen in the interest of your

community and your country. And the great thing about it is:

We, the People, can win.

__________________

Why Economic Democracy Now? The Reasons Keep Piling Up

by Matt Stannard

Development Director, Public Banking

Institute

Editor, PoliticalContext.org

PoliticalContext.org

What do a recent analysis of the Detroit bankruptcy

crisis, and recent revelations of wide-scale corporate

spying on citizen activists, have in common? They both

suggest that we need to revitalize the public sphere,

democratize economic policy, and dismantle the hierarchy

created by material inequality.

New reasons for building community power and dismantling the

power of private capital are manifest every day.

Wallace Turbeville’s November

20 report on the Detroit bankruptcy concludes

that the exacerbating factor in that city’s financial

problems–what is literally holding Detroit back from

addressing the crisis–are the risky financial instruments

with which Wall Street stuck Detroit. The “complex financial

deals Wall Street banks urged on the city over the last

several years” included interest rate swaps containing

provisions wildly favoring the banks, as well as devastating

credit rating downgrades.

An important point in Turbeville’s conclusion is the

contradiction in ethical duties present in private finance

of public endeavors.

The banks and insurance companies were in a far better

position to understand the magnitude of these risks and they

had at least an ethical duty to forbear from providing the

swaps under such precarious circumstances.

But, of course, as private corporations, the banks and

insurance companies’ main ethical duty was to their

shareholders, private investors who stood to benefit from

Detroit’s risky deal. This is, above all, a reason for

democratically-run, public finance.

Meanwhile, it’s looking like private corporations are (as

Walter Brasch once called them

in the context of consumer spying) the new “Big Brother.”

Stuart Pfiefer covered this in

the

LA Times on November 20, and both

Bill Moyers and

Democracy Now! reported on it this morning as well. From

Pfiefer’s article:

large companies employ former Central Intelligence Agency,

National Security Agency, FBI, military and police officers

to monitor and in some cases infiltrate groups that have

been critical of them, according to the report by Essential

Information, which was founded by Ralph Nader in the 1980s.

“Many different types of nonprofits have been targeted with

espionage, including environmental, anti-war, public

interest, consumer, food safety, pesticide reform,

nursing-home reform, gun control, social justice, animal

rights and arms control groups,” the report said…

The conclusion of the report’s author is serious:

“Corporate espionage against nonprofit organizations is an

egregious abuse of corporate power that is subverting

democracy,” said Gary Ruskin, the report’s author.

Revelations of corporate spying highlight the material

powers possessed by economic entities: political powers,

powers over people’s lives, “bio-power” as the Foucauldians

call it. Fighting against

state police power is hard enough. When

corporate America practice police state tactics, that fight

gets harder, because we can’t vote the violators out of

office. We can subject them to tort actions, but not the

kind of judicial review available when we’re fighting the

oppressive arm of the state.

Building accountability into our political institutions is

hard enough without the impunity and out-of-proportion power

of our financial institutions. We need the same kinds of

checks and balances in both.

__________________

Public Banks: Key to Freeing America From Wall Street?

Just one U.S. state currently has a public bank -- and it's

trouncing the competition.

by Katie

Rucke

MintPress News

In its continued fight for economic justice for the 99

percent, especially in the wake of the 2008 financial

collapse, Occupy Wall Street recently shared a

story detailing how

America can replace Wall Street financing with public banks.

While the idea of a public bank may sound far too much like

“socialism” to occur in the U.S., conservative North Dakota

has a public banking system, and studies have found that in

addition to being less corrupt, the state’s public banks are

more efficient and profitable than private banks.

Created in

1919 in the midst of

economic woes for many of the state’s farmers, the

Non-Partisan League, a populist organization, voted to

implement public banks in the Midwestern state to free

farmers from “impoverishing debt dependence.”

Some 90 years later, the bank is still in existence in North

Dakota and is reportedly thriving while it helps the state’s

community banks, businesses, consumers and students obtain

loans at a reasonable rate.

But it’s not just Occupy Wall Street advocates and

“socialists” who view public banks as a smart investment for

the nation’s economic future — some Wall Street economists

also agree public banks are a better financial choice.

Take Michael Hudson for example. Hudson is a former Wall

Street economist who

says the private

banking industry is “cannibalizing the economy,” since

private banks “are supposed to make money” and engage in

“parasitic” behavior in order to do so. Public banks, on the

other hand, “would make loans for long-term purposes to

serve the economy and help the economy grow.”

He

said when the banks

failed in 2008, the federal government should have taken

over control of the banks and began to operate them as

public banks:

“If the government would have taken over Citibank it would

not have done the kind of things that Citibank did. The

government would not have used depositors’ money and

borrowed money to gamble. It wouldn’t have gone down the

casino capitalism route. It wouldn’t have played the

derivatives market. It wouldn’t have made corporate takeover

loans.

“None of these are productive from the vantage point of

economic growth and raising productive powers and living

standards. They would not be the proper behavior of a public

bank.”

Ellen Brown is the president of the Public Banking

Institute, a group that argues there is a need for a public

bank in every state and major city in the U.S. She agreed

with Hudson and

said that if

California had public banks, the state’s economic outlook

would look much different right now:

“At the end of 2010, [California] had general obligation and

revenue bond debt of $158 billion. Of this, $70 billion, or

44 percent, was owed for interest. If the state had incurred

that debt to its own bank — which then returned the profits

to the state — California could be $70 billion richer today.

Instead of slashing services, selling off public assets, and

laying off employees, it could be adding services and

repairing its decaying infrastructure.”

Land of financial socialism

Formed in January 2011, the

Public Banking Institute

was started by financial writers, public finance experts and

former bankers to “further the understanding, explore the

possibilities, and facilitate the implementation of public

banking at all levels — local, regional, state, and

national.”

Public banks differ from private banks in that instead of

public revenue from sales taxes or property taxes being

invested in a Wall Street endeavor, a public bank reinvests

that money by investing in small businesses, public

infrastructure projects and student loans, among other

things.

PBI often points to the Bank of North Dakota as an example

of how public solutions exist as a way to end Wall Street’s

grip on the U.S. economy, since it’s the nation’s sole state

to have a public bank and has been for quite some time.

Though most states have struggled to avoid a budget deficit,

North Dakota is the only state in the U.S. that continues to

have record-setting surpluses.

According to a

press release from

May 2013, PBI reported that the BND had reported a record

$81.6 million in profits in 2012, which is the bank’s 40th

continuous year of profitability.

“Even though its Lending Services Portfolio balance

increased from $2,996 million in 2011 to $3,274 million in

2012, credit losses shrunk from $52.9 million in 2011 to

$52.3 million in 2012, indicating a healthy portfolio,” the

release said.

“The commercial loan portfolio grew from 36 percent to 40

percent of the Lending Services portfolio, representing

$1.273 billion in loans. Student loans and residential loans

decreased proportionally from 35 percent and 19 percent,

respectively, to 32 percent and 18 percent. Agriculture

loans remained at the same relative percentage year-to-year

at 10 percent, growing to $343 million in 2012 from $289

million in 2011.”

That’s not surprising for supporters of public banks, such

as those at PBI. They said that if the some

$1 trillion that is

invested in Wall Street was instead given back to the public

to support infrastructure projects, small businesses and

education, about 10 million new jobs could be created

throughout the U.S., which “would effectively end our

destructive unemployment crisis.”

“Public banks don’t speculate or gamble on high

risk,’financial products,’” Brown said. “They don’t pay

outrageous salaries and bonuses to their management, who are

instead salaried civil servants. The profits of the bank are

all returned to the only shareholder — the people.

“North Dakota is a small state,” she added. “Imagine the

returns to the people of larger states, with larger

populations and a larger volume of economic activity.”

Coming soon: End of Wall Street?

Though North Dakota has been the sole state in the U.S. thus

far to have public banks, about

20 states are

currently considering legislation to create state banks. If

more and more states start to implement such a financial

structure, Sam Knight says Wall Street may fire back by

filing a lawsuit against the banks — and Wall Street may

win.

Knight said that the activities of the BND and other state

banks may be ruled illegal because “foreign bankers could

claim the BND stops them from lending to commercial banks

throughout the state.”

But as Les Leopold wrote in an article for

Salon, since the

financial collapse activism against Wall Street has slowly

been replaced by fatalism as many advocates began to feel

Wall Street was too big and too powerful to change. However,

“this new public banking movement could have legs,” since

most Americans are still furious about how much bigwigs in

the financial industry profited from the crisis.

Brown

agrees that the more

people know about the public banks, the more likely it is

they will begin to appear throughout the U.S. “We need to

get more information out there and develop a groundswell of

popular support,” she said.

Ideally, Brown

said PBI would like

to see 50 state-owned banks and scores of county- and

city-owned banks providing low-cost banking services to 10

million currently unbanked people and over 20 million who

are underbanked throughout the United States.

__________________

Public Banking in Costa Rica: A Remarkable Little-Known

Model

by Ellen Brown

President, Public Banking Institute

Web of Debt Blog

In Costa Rica, publicly-owned banks have been available

for so long and work so well that people take for granted

that any country that knows how to run an economy has a

public banking option. Costa Ricans are amazed to hear there

is only one public depository bank in the United States (the

Bank of North Dakota), and few people have private access to

it.

So says political activist Scott Bidstrup, who writes:

For the last decade, I have resided in Costa Rica, where we

have had a “Public Option” for the last 64 years.

There are 29 licensed banks, mutual associations and credit

unions in Costa Rica, of which four were established as

national, publicly-owned banks in 1949. They have remained

open and in public hands ever since—in spite of enormous

pressure by the I.M.F. [International Monetary Fund] and the

U.S. to privatize them along with other public assets.

The Costa Ricans have resisted that pressure—because the

value of a public banking option has become abundantly clear

to everyone in this country.

During the last three decades, countless private banks,

mutual associations (a kind of Savings and Loan) and credit

unions have come and gone, and depositors in them have

inevitably lost most of the value of their accounts.

But the four state banks, which compete fiercely with each

other, just go on and on. Because they are stable and none

have failed in 31 years, most Costa Ricans have moved the

bulk of their money into them. Those four banks now account

for fully 80% of all retail deposits in Costa Rica, and the

25 private institutions share among themselves the rest.

According to a

2003 report by the World Bank,

the public sector banks dominating Costa Rica’s onshore

banking system include three state-owned commercial banks

(Banco Nacional, Banco de Costa Rica, and Banco Crédito

Agrícola de Cartago) and a special-charter bank called Banco

Popular, which in principle is owned by all Costa Rican

workers. These banks accounted for 75 percent of total

banking deposits in 2003.

In

Competition Policies in

Emerging Economies: Lessons and Challenges from Central

America and Mexico (2008), Claudia

Schatan writes that Costa Rica nationalized all of its banks

and imposed a monopoly on deposits in 1949. Effectively,

only state-owned banks existed in the country after that.

The monopoly was loosened in the 1980s and was eliminated in

1995. But the extensive network of branches developed by the

public banks and the existence of an unlimited state

guarantee on their deposits has made Costa Rica the only

country in the region in which public banking clearly

predominates.

Scott Bidstrup comments:

By 1980, the Costa Rican economy had grown to the point

where it was by far the richest nation in Latin America in

per-capita terms. It was so much richer than its neighbors

that Latin American economic statistics were routinely

quoted with and without Costa Rica included. Growth rates

were in the double digits for a generation and a half. And

the prosperity was broadly shared. Costa Rica’s middle class

– nonexistent before 1949 – became the dominant part of the

economy during this period. Poverty was all but abolished,

favelas [shanty towns] disappeared, and the economy was

booming.

This was not because Costa Rica had natural resources or

other natural advantages over its neighbors. To the

contrary, says Bidstrup:

At the conclusion of the civil war of 1948 (which was

brought on by the desperate social conditions of the

masses), Costa Rica was desperately poor, the poorest nation

in the hemisphere, as it had been since the Spanish

Conquest.

The winner of the 1948 civil war, José “Pepe” Figueres, now

a national hero, realized that it would happen again if

nothing was done to relieve the crushing poverty and

deprivation of the rural population. He formulated a plan

in which the public sector would be financed by profits from

state-owned enterprises, and the private sector would be

financed by state banking.

A large number of state-owned capitalist enterprises were

founded. Their profits were returned to the national

treasury, and they financed dozens of major infrastructure

projects. At one point, more than 240 state-owned

corporations were providing so much money

that Costa Rica was building infrastructure like mad and

financing it largely with cash. Yet it still had the lowest

taxes in the region, and it could still afford to spend 30%

of its national income on health and education.

A provision of the Figueres constitution guaranteed a job to

anyone who wanted one. At one point, 42% of the working

population of Costa Rica was working for the government

directly or in one of the state-owned corporations. Most of

the rest of the economy not involved in the coffee trade was

working for small mom-and-pop companies that were suppliers

to the larger state-owned firms—and it was state banking,

offering credit on favorable terms, that made the founding

and growth of those small firms possible. Had they been

forced to rely on private-sector banking, few of them would

have been able to obtain the financing needed to become

established and prosperous. State banking was key to the

private sector growth. Lending policy was government policy

and was designed to facilitate national development, not

bankers’ wallets. Virtually everything the country needed

was locally produced. Toilets, window glass, cement, rebar,

roofing materials, window and door joinery, wire and cable,

all were made by state-owned capitalist enterprises, most of

them quite profitable. Costa Rica was the dominant player

regionally in most consumer products and was on the move

internationally.

Needless to say, this good example did not sit well with

foreign business interests. It earned Figueres two coup

attempts and one attempted assassination. He responded by

abolishing the military (except for the Coast Guard),

leaving even more revenues for social services and

infrastructure.

When attempted coups and assassination failed, says

Bidstrup, Costa Rica was brought down with a form of

economic warfare called the “currency crisis” of 1982. Over

just a few months, the cost of financing its external debt

went from 3% to extremely high variable rates (27% at one

point). As a result, along with every other Latin American

country, Costa Rica was facing default. Bidstrup writes:

That’s when the IMF and World Bank came to town.

Privatize everything in sight, we were told. We had little

choice, so we did. End your employment guarantee, we were

told. So we did. Open your markets to foreign competition,

we were told. So we did. Most of the former state-owned

firms were sold off, mostly to foreign corporations. Many

ended up shut down in a short time by foreigners who didn’t

know how to run them, and unemployment appeared (and with

it, poverty and crime) for the first time in a decade. Many

of the local firms went broke or sold out quickly in the

face of ruinous foreign competition. Very little

of Costa Rica’s manufacturing economy is still locally

owned. And so now, instead of earning forex [foreign

exchange] through exporting locally produced goods and

retaining profits locally, these firms are now forex

liabilities, expatriating their profits and earning

relatively little through exports. Costa Ricans now darkly

joke that their economy is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the

United States.

The dire effects of the IMF’s austerity measures were

confirmed in a 1993 book excerpt by Karen Hansen-Kuhn

titled “Structural

Adjustment in Costa Rica: Sapping the Economy.”

She noted that Costa Rica stood out in Central America

because of its near half-century history of stable democracy

and well-functioning government, featuring the region’s

largest middle class and the absence of both an army and a

guerrilla movement. Eliminating the military allowed the

government to support a Scandinavian-type social-welfare

system that still provides free health care and education,

and has helped produce the lowest infant mortality rate and

highest average life expectancy in all of Central America.

In the 1970s, however, the country fell into debt when

coffee and other commodity prices suddenly fell, and oil

prices shot up. To get the dollars to buy oil, Costa Rica

had to resort to foreign borrowing; and in 1980, the U.S.

Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker raised interest rates to

unprecedented levels.

In The Gods of Money (2009), William Engdahl fills in

the back story. In 1971, Richard Nixon took the U.S. dollar

off the gold standard, causing it to drop precipitously in

international markets. In 1972, US Secretary of State Henry

Kissinger and President Nixon had a clandestine meeting with

the Shah of Iran. In 1973, a group of powerful financiers

and politicians met secretly in Sweden and discussed

effectively “backing” the dollar with oil. An arrangement

was then finalized in which the oil-producing countries of

OPEC would sell their oil only in U.S. dollars. The

quid pro quo was military protection and a strategic boost

in oil prices. The dollars would wind up in Wall

Street and London banks, where they would fund the

burgeoning U.S. debt. In 1974, an oil embargo conveniently

caused the price of oil to quadruple. Countries

without sufficient dollar reserves had to borrow from Wall

Street and London banks to buy the oil they needed.

Increased costs then drove up prices worldwide.

By late 1981, says Hansen-Kuhn, Costa Rica had one of the

world’s highest levels of debt per capita, with debt-service

payments amounting to 60 percent of export earnings. When

the government had to choose between defending its stellar

social-service system or bowing to its creditors, it chose

the social services. It suspended debt payments to nearly

all its creditors, predominately commercial banks. But that

left it without foreign exchange. That was when it resorted

to borrowing from the World Bank and IMF, which imposed

“austerity measures” as a required condition. The result was

to increase poverty levels dramatically.

Bidstrup writes of subsequent developments:

Indebted to the IMF, the Costa Rican government had to sell

off its state-owned enterprises, depriving it of most of its

revenue, and the country has since been forced to eat its

seed corn. No major infrastructure projects have been

conceived and built to completion out of tax revenues, and

maintenance of existing infrastructure built during that era

must wait in line for funding, with predictable results.

About every year, there has been a closure of one of the

private banks or major savings coöps. In every case, there

has been a corruption or embezzlement scandal, proving the

old saying that the best way to rob a bank is to own one.

This is why about 80% of retail deposits in Costa Rica are

now held by the four state banks. They’re trusted.

Costa Rica still has a robust economy, and is much less

affected by the vicissitudes of rising and falling

international economic tides than enterprises in neighboring

countries, because local businesses can get money when they

need it. During the credit freezeup of 2009, things went on

in Costa Rica pretty much as normal. Yes, there was a

contraction in the economy, mostly as a result of a huge

drop in foreign tourism, but it would have been far worse if

local business had not been able to obtain financing when it

was needed. It was available because most lending activity

is set by government policy, not by a local banker’s fear

index.

Stability of the local economy is one of the reasons

that Costa Rica has never had much difficulty in attracting

direct foreign investment, and is still the leader in the

region in that regard. And it is clear to me that state

banking is one of the principal reasons why.

The value and importance of a public banking sector to the

overall stability and health of an economy has been well

proven by the Costa Rican experience. Meanwhile, our

neighbors, with their fully privatized banking systems have,

de facto, encouraged people to keep their money in Mattress

First National, and as a result, the financial sectors in

neighboring countries have not prospered. Here, they

have—because most money is kept in banks that carry the full

faith and credit of the Republic of Costa Rica, so the money

is in the banks and available for lending. While our

neighbors’ financial systems lurch from crisis to crisis,

and suffer frequent resulting bank failures, the Costa Rican

public system just keeps chugging along. And so does the

Costa Rican economy.

He concludes:

My dream scenario for any third world country wishing to

develop, is to do exactly what Costa Rica did so

successfully for so many years. Invest in the Holy Trinity

of national development—health, education and

infrastructure. Pay for it with the earnings of state

capitalist enterprises that are profitable because they are

protected from ruinous foreign competition; and help out

local private enterprise get started and grow, and become

major exporters, with stable state-owned banks that

prioritize national development over making bankers rich.

It worked well for Costa Rica for a generation and a half.

It can work for any other country as well. Including the

United States.

The new

Happy Planet Index,

which rates countries based on how many long and happy lives

they produce per unit of environmental output, has ranked

Costa Rica #1 globally. The Costa Rican model is

particularly instructive at a time when US citizens are

groaning under the twin burdens of taxes and increased

health insurance costs. Like the Costa Ricans, we could

reduce taxes while increasing social services and rebuilding

infrastructure, if we were to allow the government to make

some money itself; and a giant first step would be for it to

establish some publicly-owned banks.

__________________

The Bank Guarantee That Bankrupted Ireland

by Ellen Brown

President, Public Banking Institute

Web of Debt Blog

The Irish have a long history of being tyrannized,

exploited, and oppressed—from the forced conversion to

Christianity in the Dark Ages, to slave trading of the

natives in the 15th and 16th

centuries, to the mid-nineteenth century “potato famine”

that was

really a holocaust.

The British got Ireland’s food exports, while at least one

million Irish died from starvation and related diseases, and

another million or more emigrated.

Today, Ireland is under a different sort of tyranny, one

imposed by the banks and the troika—the EU, ECB and

IMF. The oppressors have demanded austerity and more

austerity, forcing the public to pick up the tab for bills

incurred by profligate private bankers.

The official unemployment rate is 13.5%—up from 5% in

2006—and this figure does not take into account the mass

emigration of Ireland’s young people in search of better

opportunities abroad. Job loss and a flood of foreclosures

are leading to suicides. A raft of new taxes and charges has

been sold as necessary to reduce the deficit, but they are

simply a backdoor bailout of the banks.

At first, the Irish accepted the media explanation: these

draconian measures were necessary to “balance the budget”

and were in their best interests. But after five years of

belt-tightening in which unemployment and living conditions

have not improved, the people are slowly waking up. They are

realizing that their assets are being grabbed simply to pay

for the mistakes of the financial sector.

Five years of austerity has not restored confidence in

Ireland’s banks. In fact the banks themselves are packing up

and leaving. On October 31st,

RTE.ie reported that

Danske Bank Ireland was closing its personal and business

banking, only days after ACCBank announced it was handing

back its banking license; and Ulster Bank’s future in

Ireland remains unclear.

The field is ripe for some publicly-owned banks. Banks that

have a mandate to serve the people, return the profits to

the people, and refrain from speculating. Banks guaranteed

by the state because they are the state, without resort to

bailouts or bail-ins. Banks that aren’t going anywhere,

because they are locally owned by the people themselves.

The Folly of Absorbing the Gambling Losses of the Banks

Ireland was the first European country to watch its entire

banking system fail. Unlike the Icelanders, who

refused to bail out their bankrupt banks, in September 2008

the Irish government gave a blanket guarantee to all Irish

banks, covering all their loans, deposits, bonds and other

liabilities.

At the time, no one was aware of the huge scale of the

banks’ liabilities, or just how far the Irish property

market would fall.

Within two years, the state bank guarantee had bankrupted

Ireland. The international money markets would no

longer lend to the Irish government.

Before the bailout, the Irish budget was in surplus. By

2011, its deficit was 32% of the country’s GDP, the highest

by far in the Eurozone. At that rate,

bank losses would take every

penny of Irish taxes for at least the next three

years.

“This debt would probably be manageable,”

wrote Morgan Kelly,

Professor of Economics at University College Dublin, “had

the Irish government not casually committed itself to absorb

all the gambling losses of its banking system.”

To avoid collapse, the government had to sign up for an €85

billion bailout from the EU-IMF and enter a four year

program of economic austerity, monitored every three months

by an EU/IMF team sent to Dublin.

Public assets have also been put on the auction block.

Assets currently under

consideration include parts of Ireland’s power

and gas companies and its 25% stake in the airline Aer

Lingus.

At one time, Ireland could have followed the lead of Iceland

and refused to bail out its bondholders or to bow to the

demands for austerity. But that was before the Irish

government used ECB money to pay off the foreign bondholders

of Irish banks. Now its debt is to the troika, and the

troika are tightening the screws. In September 2013,

they demanded another 3.1 billion euro reduction in

spending.

Some ministers, however, are resisting such cuts, which they

say are politically undeliverable.

In The Irish Times on October 31, 2013,

a former IMF official warned

that the austerity imposed on Ireland is self-defeating.

Ashoka Mody, former IMF chief of mission to Ireland, said it

had become “orthodoxy that the only way to establish market

credibility” was to pursue austerity policies. But five

years of crisis and two recent years of no growth needed

“deep thinking” on whether this was the right course of

action. He said there was “not one single historical

instance” where austerity policies have led to an exit from

a heavy debt burden.

Austerity has not fixed Ireland’s debt problems. Belying the

rosy picture painted by the media, in September 2013 Antonio

Garcia Pascual, chief euro-zone economist at Barclays

Investment Bank, warned

that Ireland may soon need a second bailout.

According to John Spain,

writing in Irish Central in September 2013:

The anger among ordinary Irish people about all this has

been immense. . . . There has been great pressure here for

answers. . . . Why is the ordinary Irish taxpayer left

carrying the can for all the debts piled up by banks,

developers and speculators? How come no one has been jailed

for what happened? . . . [D]espite all the public anger,

there has been no public inquiry into the disaster.

Bail-in by Super-tax or Economic Sovereignty?

In many ways, Ireland is ground zero for the

austerity-driven asset grab now sweeping the world. All

Eurozone countries are mired in debt. The problem is

systemic.

In October 2013, an IMF report discussed balancing the books

of the Eurozone governments through a super-tax of 10% on

all households in the Eurozone with positive net wealth.

That would mean the confiscation of 10% of private savings

to feed the insatiable banking casino.

The authors said the proposal was only theoretical, but that

it appeared to be “an efficient solution” for the debt

problem. For a group of 15 European countries, the measure

would bring the debt ratio to “acceptable” levels, i.e.

comparable to levels before the 2008 crisis.

A review posted on Gold Silver

Worlds observed:

[T]he report right away debunks the myth that politicians

and main stream media try to sell, i.e. the crisis is

contained and the positive economic outlook for 2014.

. . . Prepare yourself, the reality is that more bail-ins,

confiscation and financial repression is coming, contrary to

what the good news propaganda tries to tell.

A more sustainable solution was proposed by Dr Fadhel Kaboub,

Assistant Professor of Economics at Denison

University in Ohio. In a letter posted in The Financial

Times titled “What

the Eurozone Needs Is Functional Finance,” he

wrote:

The eurozone’s obsession with “sound finance” is the root

cause of today’s sovereign debt crisis. Austerity measures

are not only incapable of solving the sovereign debt

problem, but also a major obstacle to increasing aggregate

demand in the eurozone. The Maastricht treaty’s “no

bail-out, no exit, no default” clauses essentially amount to

a joint economic suicide pact for the eurozone countries.

. . . Unfortunately, the likelihood of a swift political

solution to amend the EU treaty is highly improbable.

Therefore, the most likely and least painful scenario for

[the insolvent countries] is an exit from the eurozone

combined with partial default and devaluation of a new

national currency. . . .

The takeaway lesson is that financial sovereignty and

adequate policy co-ordination between fiscal and monetary

authorities are the prerequisites for economic prosperity.

Standing Up to Goliath

Ireland could fix its budget problems by leaving the

Eurozone, repudiating its blanket bank guarantee as “odious”

(obtained by fraud and under duress), and issuing its own

national currency. The currency could then be used to fund

infrastructure and restore social services, putting the

Irish back to work.

Short of leaving the Eurozone, Ireland could reduce its

interest burden and expand local credit by forming

publicly-owned banks, on

the model of the Bank of North

Dakota. The newly-formed

Public Banking Forum of Ireland

is pursuing that option. In Wales, which has also been

exploited for its coal, mobilizing for a public bank is

being organized by the

Arian Cymru ‘BERW’

(Banking and Economic Regeneration Wales).

Irish writer Barry Fitzgerald, author of

Building Cities of Gold,

casts the challenge to his homeland in archetypal terms:

The Irish are mobilising and they are awakening. They hold

the DNA memory of vastly ancient times, when all men and

women obeyed the Golden rule of honouring themselves, one

another and the planet. They recognize the value of this

harmony as it relates to banking. They instantly intuit that

public banking free from the soiled hands of usurious debt

tyranny is part of the natural order.

In many ways they could lead the way in this unfolding, as

their small country is so easily traversed to mobilise local

communities. They possess vast potential renewable

energy generation and indeed could easily use a combination

of public banking and bond issuance backed by the people to

gain energy independence in a very short time.

When the indomitable Irish spirit is awakened, organized and

mobilized, the country could become the poster child not for

austerity, but for economic prosperity through financial

sovereignty.

__________________

The Money Monopoly

by Mike Krauss

Member of the Board of Directors, Public

Banking Institute

Chair, Pennsylvania Public Banking

Project

www.papublicbankproject.org

OpEdNews

In a masterful study of the Federal Reserve, Secrets of

the Temple , William Greider observed that the average

American farmer in 1880 knew more about banking and money

than most U.S. college graduates today.

Let me prove that.

Take a bill from your wallet or purse. Read the side with

the portrait. It says very clearly at the top, "Federal

Reserve Note."

The Federal Reserve is not a part of the federal government.

It receives no appropriation from Congress. It is a private

corporation and its stock is privately traded. The

stockholders are the member banks of the regional Federal

Reserve Banks, so its major stockholders are the largest

banks and their owners.

Historically these have been the powerful Wall Street and

European banking families: think Rothschild, Warburg,

Morgan, Rockefeller.

All the bills and coins in circulation today are a tiny

fraction of the supply of money in the American economy. All

the rest is credit, created on the books of the banks "ex

nilo" -- out of nothing.

This money comes into circulation at interest paid to the

banks that create it. A central bank like the Federal

Reserve creates the money supply of the United States, at

interest.

The Bank of England was the first privately owned central

bank to control a nation's currency. One of its owners, of

the Rothschild family well understood what that meant and

said: "Give me control of a nation's money, and I care not

who makes the laws."

Big money.

The colony of Pennsylvania escaped the clutches of the Bank

of England and its tax on money by printing its own. It was

pure genius.

Writing in The Wealth of Nations in 1776, Adam Smith

noted: "The government of Pennsylvania, without amassing any

treasure [gold or silver] invented a method of lending, not

money indeed, but what is equivalent to money. By advancing

to private people at interest " paper bills of credit "

legal tender in all payments " it raised a moderate revenue

which went a considerable distance toward defraying the

whole ordinary expense of that frugal and orderly

government."

Until the mid 1750s there was broad prosperity in

Pennsylvania. On a trip to London, Ben Franklin let the cat

out of the bag. He noted the widespread poverty he saw there

and explained how by printing their own money and avoiding

the need for the notes of the Bank of England to conduct

their commerce, the people of Pennsylvania insured their own

prosperity.

The private owners of the Bank of England went the 1700s

version of ballistic and lobbied King and Parliament (Sound

familiar?) to outlaw this colonial "script." The depression

that followed was the cause of the American Revolution.

Franklin wrote, "In one year the conditions were so reversed

that the era of prosperity ended, and a depression set in,

to such an extent that the streets of the Colonies were

filled with unemployed."

He concluded, "The Colonies would gladly have borne the

little tax on tea and other matters, had it not been the

poverty caused by the bad influence of the English bankers

on the Parliament [Again, sound familiar?]: which has caused

in the Colonies hatred of England, and the Revolutionary

War."

The bankers got control. Hamilton fronted for

them in the young United States. Jefferson and Jackson

fought them. Lincoln fought them. Lincoln was assassinated,

the bankers once again had control and the war for control

of the nation's supply of money raged on.

After decades of planning and massive PR and propaganda,

having bought up the support of Ivy League scholars,

journalists and the requisite number of votes in Congress,

the Wall Street cartel and their foreign allies pushed

creation of the Federal Reserve through Congress and got

complete control of the nation's money and credit.

Before you pay your taxes, the money you pay with has

already been taxed by the owners of the Federal Reserve,

which for over 100 years have diverted trillions of dollars

of interest payments on our money from the American people

into their own pockets.

That is what "central banks" are designed to do: extract

wealth from nations by monopolizing the supply and cost of

money and credit.

The debt ceiling, sequestration, austerity and budget

deficit are a diversion. The U.S. Congress can slash the

debt by taking back control of our money from the Federal

Reserve monopoly and returning it to the U.S. Treasury and

the American people, as the Constitution (Article I, Section

8) wisely provided.

|